Anglim Gilbert Gallery

Katherine Sherwood | Brain Flowers

For over seven years, Katherine Sherwood’s work has recontextualized still life painting tropes and Western art historical representations of the female nude.

Her lush depictions of human and botanical forms typically incorporate medical imagery, including, the artist’s own MRI brain scans. Sherwood’s Venuses of the Yelling Clinic are distinctly varied in skin tone, body type, and physical ability. Her figures recline in a markedly relaxed manner, sometimes wearing a leg brace or carrying a walking aid – visibly free from the sexually expectant, male-centric gaze of her source material. These subtle and overt alterations highlight the abelist, Euro-centric conceptions of beauty that have dominated the study and writing of Western Art History for centuries.

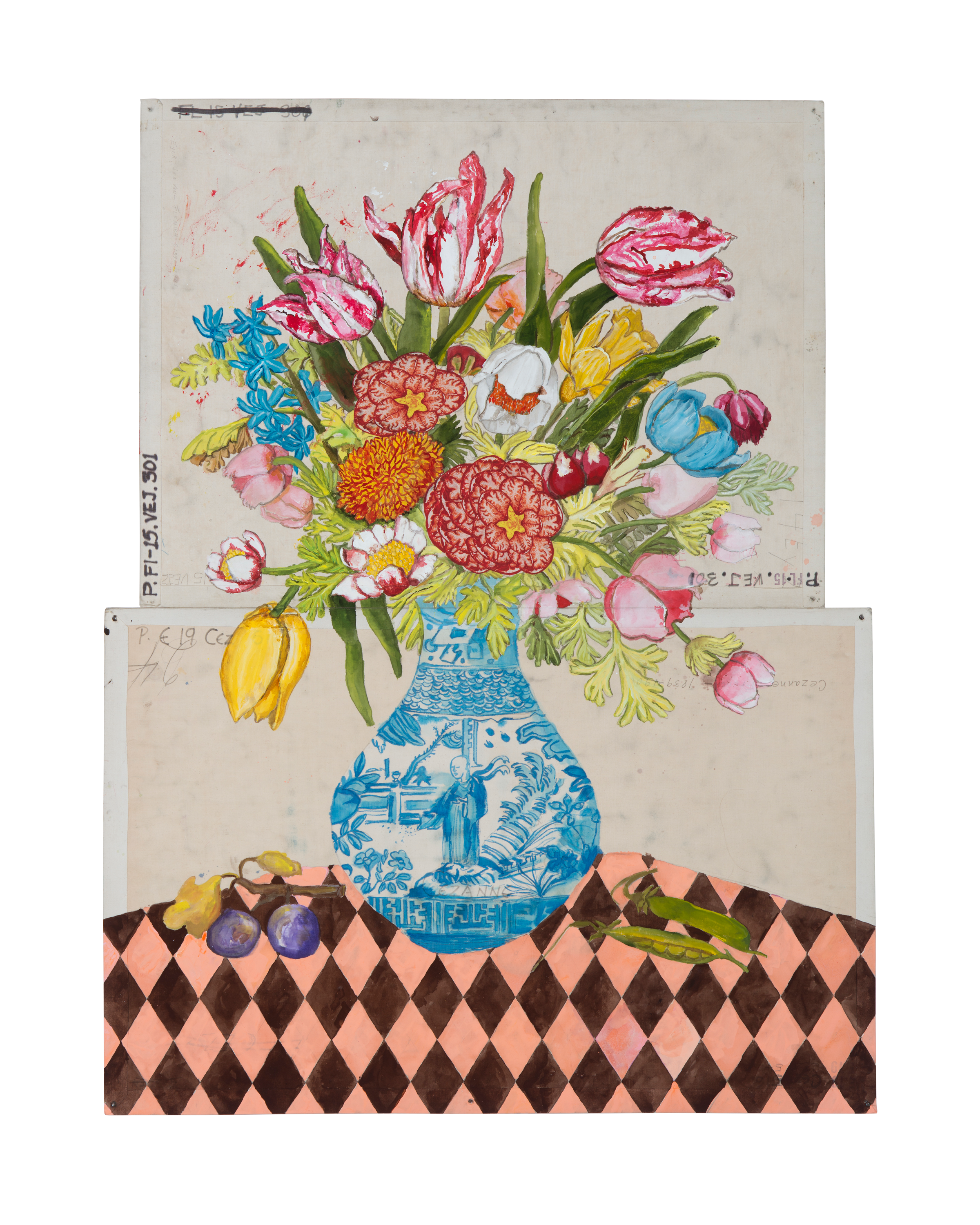

Sherwood’s examination of these long-held biases takes place in every facet of her artistic process. She takes great care to utilize physical material, appropriate imagery, and alter subject matter in a manner that gracefully subverts problematic visual traditions. Painting directly on the flat, cotton backs of discarded artistic reproductions, Sherwood makes direct reference to education’s role in communicating how we assign cultural value and to whom. The reproductions, once used as teaching aids in Art Practice courses at UC Berkeley, where Sherwood is Professor Emerita, become physical evidence of the art historical canon’s many limitations.

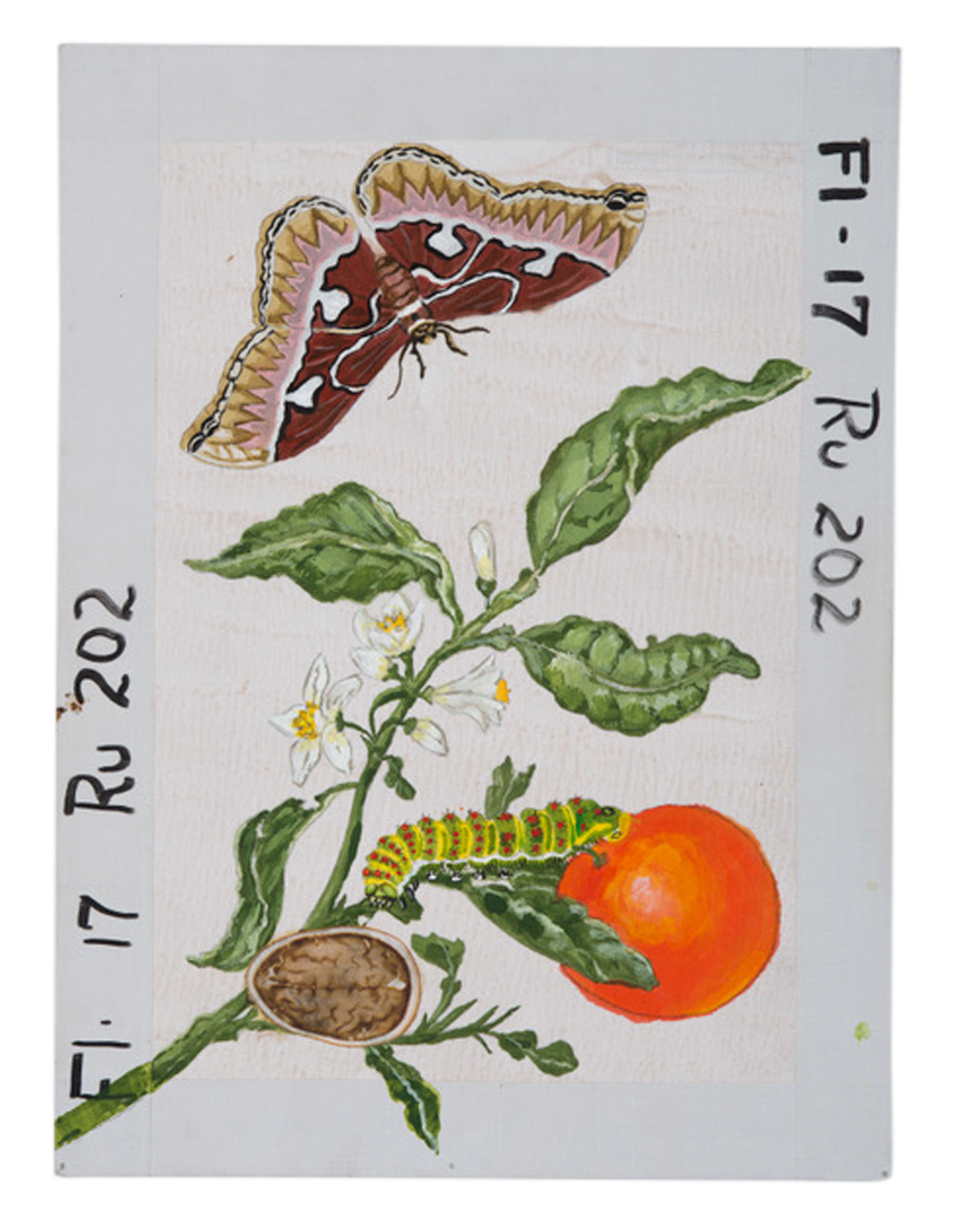

Sherwood’s insightful depictions of disability and use of found material, are further deepened by her ongoing homage to women artists of the 17th century Baroque period. Her series, Brain Flowers, borrows imagery from the works of Maria van Oosterwyck, Maria Sybilla Marian, Rachel Ruysch, Josefa de Obidos, and Giovanna Garzoni, among others. Sherwood’s interpretation of traditional vanitas paintings are twofold. Not only does she give new life to the work of women artists before her, who rarely received due recognition in their time, but she also speaks to the power of survival in the face of harsh certainties.

Sherwood uses the genre’s historical language, wherein opulent floral arrangements and table scenes allude to the inevitability of death, but to a more nuanced end. Ultimately, the incorporation of brain imagery lends these works a sense of transience. She writes, “If the skull suggests death in these historical paintings, then what do brains do? I used to think my use of brain-related imagery was an indicator of joyous life, but as time passes, I see its utility as a representation of life and death.”